Honor your hero with thoughts, memories, images and stories.

Forrest V. “Lefty” Brewer was born in Sequatchie, Tennessee, about 30 miles northwest of Chattanooga. The Brewers were a nomadic family—relocation was to become a familiar thing — and in 1924, parents Frank and Mattie Brewer loaded up the family Dodge with five-year-old Forrest and his siblings—Vera, Frank, Jr., Kate and William—along with their scant few possessions and moved 600 miles south to Orange City, Florida. As it was for many families during the Depression, times were hard for the Brewers. They were an impoverished family, moving from town to town, and slum to slum, where street fights were commonplace and electricity was not. Frank Brewer, a man troubled by alcohol, ran a succession of failed grocery stores. When the business failed, the family moved on and his wife, Mattie, eventually became the breadwinner, operating a boarding house for railroad workers from the Seaboard Railway in the Lackawanna neighborhood of Jacksonville, Florida. The Brewer children, nonetheless, were impervious to their hardships. Their days were spent hunting rabbits and squirrels, and fishing for copperhead bream, bass and catfish. However, Forrest had a propensity for getting in trouble that remained with him all his life. “He was not a trouble maker,” recalled his younger brother, William. “It just seemed to follow him.” On one occasion, Forrest stole a watermelon from a neighbor’s yard. He was soon caught and the neighbor made such a fuss that, for a time, William thought his brother was going to jail. Another time, a neighbor was painting an old washing machine and warned the Brewer boys not to touch it. Forrest could not resist and left fingerprints all over the wet paint resulting in the neighbor chasing Forrest, with paint brush in hand, all the way down the street. Sports were a big thing for the Brewer boys. Nearby Lackawanna Park provided a swimming pool, basketball court, horseshoe pits and football field encompassed by a running track. Forrest—or Lefty as he was known to everyone—was the gifted athlete of the family. He was coordinated, fast and agile, and the best player in neighborhood sandlot ballgames played with two sack bases and home plates made out of tin. Brewer became a stellar pitcher with the Robert E. Lee High School team, and at the ballfield near the city incinerator, he fine-tuned his pitching skills with the Smith’s Service Station team in the City League. He also played softball and pitched for the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad team where he worked after dropping out of high school. In the spring of 1938, 19-year-old Brewer—along with infielder Faulene Kirkland, who also played for Smith’s Service Station—attended a baseball training school conducted by veteran minor leaguer John “Poke” Whalen, and general manager of the Florida Coast League’s St. Augustine Saints, Fred Hering. They needed just one look at Brewer’s deceptive yet smooth delivery, his overpowering fastball and hard-breaking curve before offering him a contract with the Class D Saints. Under the watchful eye of veteran catcher Allen Mobley and player-manager and former major leaguer Lyle Judy, Brewer turned in a truly memorable rookie performance. Francis Field, home of the Saints, was a magical place during the summer of 1938. With the smell of roasted peanuts filling the air, and the rhythmic sounds of soda bottles banging against wooden bleachers during late inning rallies, Brewer unleashed a season of blistering fastballs on his way to an incredible 25 wins. In 41 appearances, he easily led the league in wins and strikeouts with 234, while his 1.88 earned run average, best among left-handers, was third best in the league. Brewer completed 28 of the games he started, hurled four shutouts, and was selected to the all-star team on the way to becoming a local hero. William Brewer, who was 14 at the time, was in awe of his older brother’s success as a professional baseball player. “Kate and I started a scrapbook,” he recalled, “and we would gloat over his deeds on the mound. We were so proud of what he did. I would go to school with one of his write-ups in my pocket, dangling out for everyone to see. I was to become known more and more as ‘Lefty Brewer’s brother’ and I reveled in it.” Brewer’s performance made quite an impact on the baseball world. “When future historians prepare their texts on Florida State League history,” proclaimed league secretary, Peter Schaal, at the conclusion of the 1938 season, “you can bank on it that the antics of one Forrest ‘Lefty’ Brewer ... will occupy a major portion of the space assigned to the hurling heroes. Brewer is easily the greatest young prospect ever to go out of the Florida State League.” At Orlando, on June 6, 1938, Brewer hurled the masterpiece of his brief career. His eldest sister, Vera, was living in DeLand at the time and usually attended Brewer’s games at Orlando. But on this day, Vera was guest of honor at a birthday party. Brewer called his sister that afternoon, wished her a happy birthday and reminded her to tune in the radio broadcast of the game. “I’ll pitch a real special one tonight,” he said, “since it’s your birthday.” Vera had the radio tuned in to the broadcast from Orlando, but what with the birthday celebration going on, it was the seventh inning before she realized that Orlando had not made a single hit off her brother. “From that point on, you could have heard a feather floating in our living room,” she recalled. “We listened—hardly daring to breath lest we jinx him—as one after another Orlando men went down hitless.” That night, Brewer was carried from the field on the shoulders of his teammates after beating the Orlando Senators, 3–0. He walked one and struck out 14 in achieving the Florida State League’s only no-hitter that year. Despite Brewer’s 25 wins and another 16 contributed by Carl Weigle, the St. Augustine Saints finished the season in fifth place with a 70–70 record and no hope of a playoff position. Nevertheless, news of the young left-hander’s heroics spread fast and Clark Griffith, owner of the American League’s Washington Senators, purchased Brewer’s contract and invited him to the capital city for the final weeks of the 1938 season. Although Washington was a perennial second division team, Brewer got to see major league baseball for the first time and the great Dutch Leonard in action. When Brewer returned home to Jacksonville in October, he had saved enough money not to have to work and spent much of his time hunting and fishing, and occasionally pitching games for local semi-pro teams. In 1939, he was with the Washington Senators for spring training in Orlando, Florida, but was released to the Charlotte Hornets of the Class B Piedmont League in March. After pitching just three games and suffering two defeats, manager Cal Griffith felt the 20-year-old was not ready for Class B ball and released him to the Shelby Nationals of the Class D Tar Heel League. His sophomore year was to be plagued with arm problems, probably because of overuse the previous season. Five wins in 19 appearances with Shelby and an inflated ERA of 5.25 triggered a return to the Florida State League in July. Toiling for the Orlando Senators—against whom he threw his no-hitter the previous year—Brewer recorded seven wins with 11 losses and a 3.85 ERA. In 1940, Brewer was back with the Charlotte Hornets, and as Hitler’s blitzkrieg swept through Europe at an alarming rate, he turned in a steady performance, quickly becoming a fan favorite at Hayman Park. On a team that lacked offense and finished fifth, he won 11 games against nine losses. On May 11, he defeated the Durham Bulls, 2–1. On July 9, he defeated the Norfolk Tars, 4–2, on five hits, and on July 20, he beat the Rocky Mount Red Sox, 3–2, holding them to four hits. In August, the Hornets made a run for fourth place and a position in the playoffs. Brewer responded by pitching his best game of the year on August 25, defeating Norfolk, 1–0, and allowing just two hits. While Charlotte failed to make the playoffs, Brewer’s pitching again caught the eye of Clark Griffith who invited him back to Washington for the end of the season. Following President Roosevelt’s signing of the Selective Training and Service Act in September 1940, the Charlotte Observer announced that 10 Hornet players were eligible for the first wave of conscription, including Brewer. On March 4, 1941 — one week before reporting to the Senators’ spring training camp — he entered military service with the Army at Camp Blanding, Florida. At the age of 22, and on the verge of a major league career (he was carried on the Washington Senators’ National Defense Service List), he swapped flannels for service fatigues and reported for basic training. Brewer remained at Camp Blanding with the 31st “Dixie” Infantry Division until volunteering to serve with the paratroopers in January 1942. He was enticed, perhaps, by their elitism, but certainly by the extra $50 a month hazardous-duty bonus. Brewer attended Parachute Jump School at Fort Benning, Georgia, and after twoweeks of preliminary training, the first jumps were made from 35-foot towers by dropping down on a pulley into a pit of sawdust. Once that technique was mastered, they moved on to the 250-foot towers, where they were attached to a static line and would drop by parachute. The next step was to jump from an airplane and after five jumps Brewer earned the coveted silver wings of a paratrooper. Brewer remained at Fort Benning throughout the summer months and regularly pitched for the baseball team that was defeated only twice all season, both times by Camp Wheeler. On one occasion it was former Senators shortstop Cecil Travis who broke up the game for Camp Wheeler, hitting a double off Brewer with the bases loaded. “He told me after the game,” Brewer later explained, “that I shoulda known better than try and sneak an outside curve past him like that. But I told him that he was the first left-handed hitter that I couldn’t get on that pitch.” While stationed at Fort Benning, Brewer liked to return home to his family as often as possible and one occasion proved to be a special moment. “One of the strangest events occurred to me when I got off the bus in Jacksonville,” recalled younger brother William, who was serving with the Navy and returning home on furlough. “The first thing I needed to do was go to the men’s room [at the Jacksonville bus station]. When I entered, there stood my paratrooper brother, Lefty.” The two brothers had no idea their furloughs coincided, and arrived together at their parent’s home, where they were met with looks of shock and elation. It was a wonderful, if short-lived, reunion. While military life suited Brewer (he rapidly rose to the rank of staff sergeant), he also enjoyed the comforts of home and would sometimes stay over on leave. “Once he got all the way to the train station,” recalled William, “thumbed his nose at the departing train and went back home.” A local girl named Mary Dixon was another reason for Brewer wanting to stay home. They had been dating for some time, and during the summer of 1942, they got married at the small town of Macclenny, west of Jacksonville. Brewer became a platoon sergeant with Company B of the newly formed 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR) at Camp Blanding in October 1942. “I first met Staff Sergeant Brewer in October of 1942,” explained Bill Dean. “[He] was part of the experienced cadre waiting for us recruits to dribble in from recruiting stations all over the United States. [He] had already been through the Fort Benning jump school and was wearing the airborne wings and highly polished jump boots, and was an imposing figure for we pink cheeked kids to gaze upon. As if all those attributes were not enough, he had also played professional baseball. Lefty was my platoon sergeant all through the three weeks of basic training, and I cannot say enough about what a great guy he was. He even brought some culture into my life during off-duty hours in our barracks. Rudyard Kipling’s ‘Gunga Din’ was a favorite poem of his, and he would recite it with such gusto while cleaning his rifle or shining his boots, that most of us rookies would stop everything and take it all in with rapt attention.” In April 1943, the 508th PIR relocated to Camp Mackall—at the time, it was merely a name assigned to a few buildings and upturned soil between Pinehurst and Rockingham in North Carolina. Camp Mackall, however, was to become a marvel of wartime construction. Within four months, 62,000 acres of wilderness had 65 miles of paved roads, a 1,200-bed hospital, five movie theaters, a complete all-weather airfield and 1,750 buildings. Training was vigorous for the paratroopers at Camp Mackall. They made day and night jumps as the 508th PIR was developed into a smooth functioning team. On one occasion, as Brewer was about to board a plane for a practice jump, he thought he recognized the pilot. Upon closer inspection, he discovered it was the Senators former third baseman Buddy Lewis. It was in Jacksonville around this time that William saw his brother Lefty for the last time. “Lefty was at the Dixon’s house with his wife, Mary,” he explained. William had orders to report to the Naval Air Station at Jacksonville at 2:00 A.M., and went over to say farewell to his brother. “They were sleeping in the corner bedroom. Their window was open and I woke them up to say good-bye. His last words to me were, ‘I’ll see you, William.’” During the summer of 1943, Brewer had an opportunity to limber up his pitching arm with the 508th Red Devils. The ball team was strong and the line-up was dotted with minor leaguers including Frank Labuda, John McNicholas and Frank Shank. Brewer shared pitching duties with Okey Mills, a colliery league pitcher from West Virginia, and the Red Devils played all through the long, hot summer during off-duty hours. “We are really having a good season,” Brewer wrote in a letter to his mother. “We have won 14 and only lost three. And I have won 10 and haven’t lost any. When the war is over I am really going to town, my arm is in better shape than it has ever been before. Yesterday I pitched a one hit game and know [sic] runs.” However, the letter to his mother also revealed that, just like in his childhood, trouble seemed to be not too far behind. “I will be able to pay you some of the money back I borrowed,” he wrote, “ but not all this payday, because they are taking $50.00 out of my pay for getting in a fight with a soldier from the glider troops and I broke his jaw and they are taking it to help pay the bill. It wasn’t my fault but they are doing it anyway.” The fight meant that Brewer lost his rating as a staff sergeant. He was busted to the lowly rank of a private and transferred to Company A so he could get his rating back sooner. The 508th Red Devils had a 26–4 won-loss record in 1943, and clinched the Camp Mackall championship by defeating the 135th Quartermaster Company in the league playoffs. Shortly afterwards, a regimental order disbanded the team because it was felt that further play would result in the loss of valuable military training for the men. Had the season continued, it is likely that the Red Devils would have attained national prominence as games had been scheduled against the North Carolina Pre-Flight Cloudbusters and the mighty Norfolk Naval Training Station, where Phil Rizzuto and Dom DiMaggio were playing their service baseball. In November 1943, Brewer was preparing to be posted overseas and made one last visit to his wife and family in Jacksonville. Judith Frierson Hunter, Brewer’s niece, was eight years old at the time and remembers her uncle’s last visit home. “The whole family was together,” she recalled. “I was in awe of everything military and Lefty gave mehis paratrooper’s wings to ‘keep for him.’ How proud I was of my handsome uncle who was going to be a big-league baseball star after the war.” At 24 years old and a veteran of 18 jumps, Brewer admitted to the Charlotte Observer in 1943 that he was still in a sweat before every jump. “Some fellows say that they get used to jumping,” Brewer said, “but don’t you believe it. Every time you get up to the door of that plane and look out into space you get the same old feeling. And if you ain’t looking, you just sit there and you know that there’s a big hunk of air out there. I love my wife, but I told her there was one thing that I loved even more—and that was seeing that parachute opening up over my head.” On December 8, 1943, Brewer, who had attained the rank of corporal and was now with 1st Battalion, Headquarters Company, wrote his last letter home from Camp Mackall in which he expressed his doubt of what lay ahead for him. “Sure hope to get home for Christmas,” he wrote, “but one’s never certain these days.” His doubts were realized when, on December 20, 1943, the 508th PIR moved to Camp Shanks, New York, in preparation for overseas deployment. The men were given passes for two nights in New York over Christmas and were then loaded onto the USAT James Parker on December 27. They arrived in Belfast, Northern Ireland, on January 8, 1944, and camped in the small town of Port Stewart. The regiment was attached to the 82nd “All American” Airborne Division and participated in night training maneuvers while waiting for the inevitable invasion of mainland Europe. “It rains here all the time and I sure would like to see the Florida sunshine again,” Brewer wrote home in January 1944. But in an optimistic light, he noted, “I don’t know when the big push is going to start but it can’t last long after it does.” A letter home dated March 7, 1944, emphasized the boredom that was setting in among troops in Northern Ireland. “The weather is terrible here, rain, snow and sleet all the time, I sure am fed up in Ireland.” The same letter also explained how Brewer was still struggling to keep out of trouble. Having been previously busted from staff sergeant to buck private, he had made his way back to corporal before getting in trouble again. “I guess you see where I’m a private now,” he wrote. “I was on pass and a few hours late getting back, well it’s happened before.” In March 1944, the 508th PIR left Northern Ireland for Scotland, then traveled by rail to Nottingham, England. They participated in a couple of night jumps and trained hard, but enjoyed the nightlife that the city of Nottingham had to offer. Nottingham had a population of 250,000 at the time and downtown was just ten minutes walk from where the 508th PIR was camped at Wollaton Park. The gregarious young paratroopers, immaculate in their resplendent uniforms and jump boots, made a favorable impression with the local community and, on many evenings, when the landlord of the local pub called “time,” Brewer, fueled by a few beers, would get up on a chair to brilliantly and emotionally recite the saga of “Gunga Din.” Brewer was far happier in England. “I like it much better here than I did in Ireland,” he wrote home on March 30, 1944. “I wish I was able to tell you about the place ... but you realize that would never do.” Baseball was also on his mind at the time. “I sure would be glad to go to Spring Training. I will make it next year.” On Sunday, May 28, 1944, the 508th Red Devils baseball team unexpectedly reformed for their final game before going into combat. Speculation still hangs over the reason this game was staged. The “official” story at the time was that the Nottingham Anglo-American Committee requested the Americans to stage a sporting event because the people of Nottingham had for years been void of entertainment. However, because the game was arranged by Brigadier General James M. “Jumpin’ Jim” Gavin, commander of the 82nd Airborne Division, many believe the game was designed to fool the Germans. If American paratroopers were playing baseball in England, how could an be imminent? May 28, 1944, was a beautiful day and an enthusiastic crowd of 7,000 fans gathered beneath clear blue skies at Meadow Lane soccer ground to see the 508th Red Devils play the 505th PIR Panthers. A photograph of the Red Devils shows how unprepared they were for the game. Wearing jump boots, combat fatigues and vests, the ballplayers have an almost bewildered look on their faces as they pose for the camera, each man wearing a number pinned to his vest for easy identification when the photos were sent back to their hometown newspapers. Okey Mills started the game on the mound for the Red Devils and was relieved by Brewer in the fourth inning. With his deceptive pick-off move, Brewer picked off the first two men that got on base. The Red Devils outclassed the Panthers, 18–0, and the Nottingham Guardian the next day described how the teams “played with extraordinary vigor,” and noted there was “spectacular hitting, some magnificent catches and many exciting incidents.” Nevertheless, there had been a noticeable absence of paratroopers in the stands at the game. Having been such a familiar sight in Nottingham for the last couple of months, only officers and players were on hand. As the crowd cheered each crack of the bat, the rest of the regiment made a 40-mile journey to Folkingham Airfield where it was sealed in amidst tight security. Preparations for the invasion had begun. Folkingham, like many other airfields around England at the time, was a hive of activity. The runways were packed with Douglas C-47 transport planes adorned with black and white invasion stripes, and groups of paratroopers meticulously studied maps of the drop zones in Normandy. They packed equipment, cleaned rifles, played cards and shot dice in the hangar buildings, attended movies, wrote letters to loved ones, and learned of their objective: to keep the Germans from reinforcing troops that were defending the beaches. In his last letter home to his parents, Brewer expressed his joy to be back with Company B, writing, “I am back in my old company, a private, but it’s worth it to be back with the boys I started with.” In closing, Brewer reassured his family: “Don’t any of you worry about me, just keep your fingers crossed for me as you did at the ball games and I will be all right.” On June 4, they were ready to take off but the weather forced a delay. The following night, eight days after pitching for the Red Devils, Brewer and the men of the 508th — with their faces blackened and hearts racing — boarded C-47s for the flight across the English Channel. D-Day had begun and the paratroopers would spearhead the invasion. C-47s were stark inside. A row of hard metal bucket seats lined both sides of the plane and the roar of the engines drowned out any attempt at conversation as they trudged through the dark skies towards the Normandy coast. Once over the mainland of France the sky became illuminated with searchlights and deadly tracer bullets pierced the wings and fuselage of the unarmed and unarmored planes. Anti-aircraft fire exploded all around as they neared their drop zones at an altitude of 400 feet. When the red light over the door of the plane flashed on, everybody stood up and clamped themselves onto the cable that ran down ceiling of the plane. Amidst yells of “Go! Go! Go!” Brewer and 24,000 Allied paratroopers just like him descended through the darkness into chaos and confusion. Inexperienced pilots had failed to locate the drop zones and the majority of the 508th PIR found themselves too far east and astride the flooded Merderet River with the enemy all around. First Sergeant Adolph “Bud” Warneke was in the same plane as Brewer. “We jumped together about 2:20 A.M.,” he explained. “It was dark and we were all scattered out for a while. About five o’clock that morning Lefty came in to where we were assembling. He brought ten men in with him. Things were pretty messed up and plenty of confusion.” The assembly point was close to the La Fière manor, a half-dozen heavy stone farm buildings enclosed in a five-foot wall, which stood on the east bank of the Merderet River, about two miles east of the original drop zone at Picauville and two miles west of Sainte-Mère-Eglise, the first French town to be liberated by American forces. German troops were entrenched at the manor and the paratroopers made an attack at about noon. Brewer was a squad leader, and in the words of Bill Dean, who had served with Brewer for more than two years, “One helluva fire fight erupted.” Despite heavy resistance the attack was successful and the paratroopers then followed the causeway to the bridge that spanned the river to join the rest of the 508th. At about 2:30 P.M., they were counterattacked by an overwhelming German force of tanks and heavily armed infantry that blocked the paratroopers return across the bridge. “We got hit pretty hard,” recalled Warneke. “There were too many so we had to move back. There was a lot of confusion while we were getting hit. They threw a lot of artillery and mortar.” Trapped in a hail of gunfire and explosions, Brewer ran for his life towards the river. Bill Dean was running as hard as anyone. “As I ran for the river,” recalled Dean, “I was aware someone was running hard just behind me, and in my panic I took a quick look and saw Lefty, at port arms, running like he was going to stretch a triple into a home run.” A split second later, there was a burst of machine-gun fire and Brewer pitched forward, face down into the river. Exactly six years after pitching a no-hitter with the St. Augustine Saints, Lefty Brewer’s life ended. Brewer was reported missing in action following D-Day, and for four agonizing months, his family held on to a glimmer of hope that he could still be alive. Even when news from the War Department in October confirmed his death, his mother refused to accept that her son was gone. “It is only natural that you should hope some mistake has been made,” wrote Colonel Roy E. Lindquist, commanding officer of the 508th PIR, to Mrs. Brewer in November 1944. “And it is barely possible that such is the case, but if I were you I would not depend on it too much. ‘Lefty’ was one of the best known and liked men in this regiment,” Lindquist continued. “He pitched for our baseball team and was largely responsible for the success of that group. He carried the same fine principles of sportsmanship with him in his work as a soldier.” In a letter to Brewer’s sister, Vera, in 1945, Bud Warneke said, “He made army life cheerful instead of what it is. When he went I lost the best friend I ever had.” Private Forrest Brewer was buried at the American Cemetery in Sainte-Mère-Eglise, along with four other members of the 508th baseball team slain in the battle for Normandy: Private First-Class Rene Croteau, Sergeant John Judefind, Corporal William Maloney and Private Elmer Mertz. That month, Brewer’s younger sister Kate sent news of his death to Senators owner Clark Griffith. “I want you and your entire family to know that I mourn along with you at the loss of this fine boy,” wrote Griffith in his reply. “Forrest was such a fine upstanding young man and Calvin [Griffith, vice president of the Senators] and myself and all connected with the Washington club dearly loved him.” In 1947, at the request of the family, Brewer’s body was returned home to Jacksonville, Florida. Following services at Key McCabe Funeral Homes, the flag-draped coffin was carried past the ballfield where he learned to pitch and was laid to rest at the Riverside Memorial Park Cemetery. Among the pallbearers were minor league ballplayers Ray Headon, Jones Thurmond and Saints teammate Faulene Kirkland. Fifty years later, Bill Dean, the paratrooper who was with Brewer the day he died, admitted that not a day went by when he did not remember his comrade. “I will never forget Lefty,” said Dean, “...nor how fickle fate is ... he taught me how to soldier and I made it back ... he didn’t.” In November 1988, Brewer was inducted in the Jacksonville Sports Hall of Fame for his "outstanding athletic achievements." To most sports fans, Lefty Brewer's name remains as unfamiliar as his career remains incomplete - another bush leaguer who failed to make it the "The Show." But his ultimate sacrifice in the line of duty should not be forgotten, and thanks to baseball's unique statistical documentation, the brief career of this American hero will always remain an integral part of the national pastime.

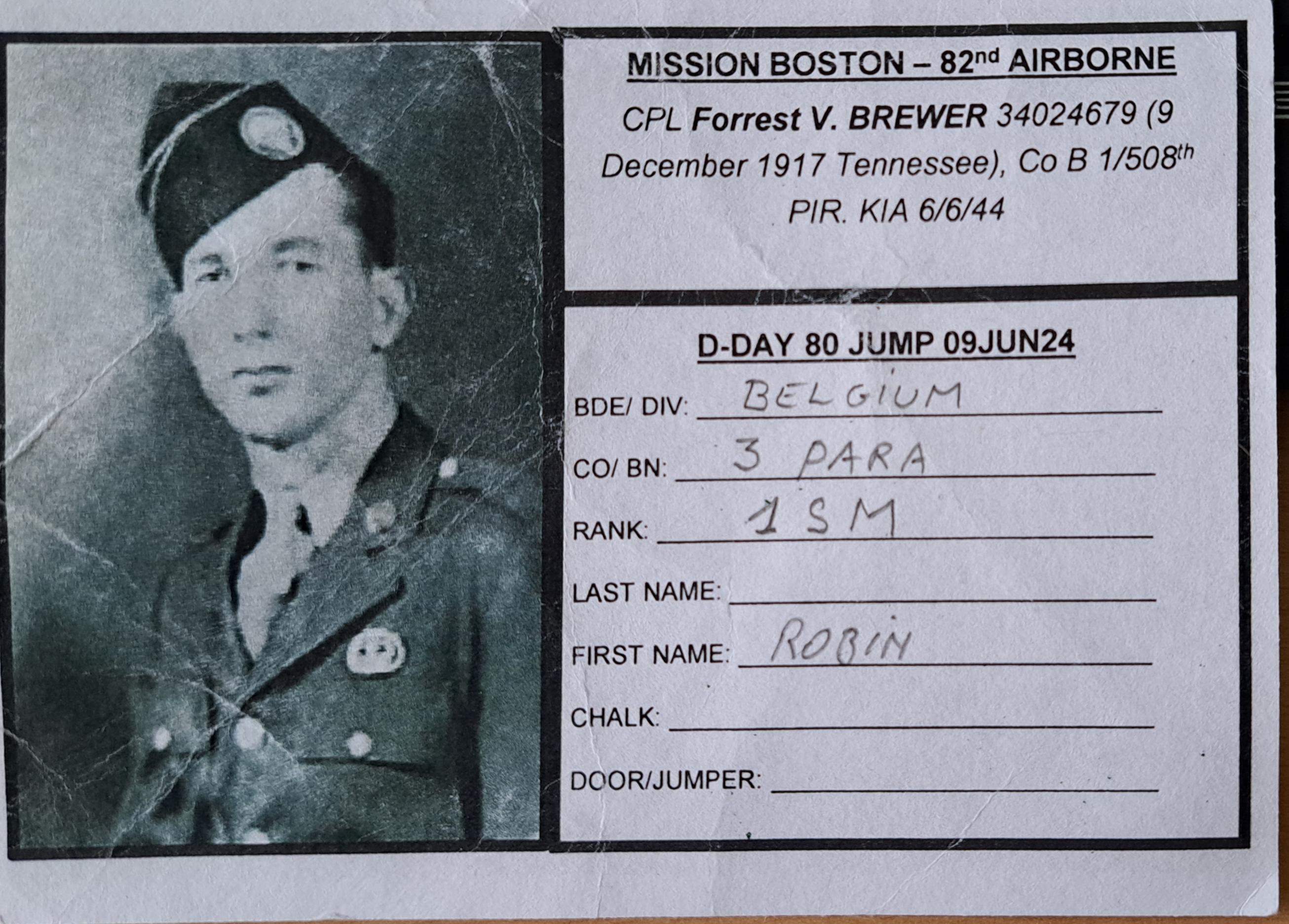

Your picture was jumped on the La Fière dropzone in Normandy, on 6/6/2024. Thank you for our freedom!